I’m curious how the English pronunciation mnemonics are chosen. For example, the 出 character suggests the horror movie character ‘Chucky’ to remember the character is pronounced ‘choo’. But Chucky is pronounced like ‘chuh’ not ‘choo.’

This issue persists across all the characters I’ve learned so far; Using pop-culture characters whose names begin with the English consonants, but do not have the pronunciation that is being taught in the lesson at all (i.e. [Le]golas (lay) for 了(le), [Yo]shi (yo) for 一 (yi), or [En]glish Manor (eeng) for 朋 (éng).

Yeah, there’s sometimes a little bit of disconnect. It can be hard to find a universal good fit that everyone knows.

That said, it’s also important for the sake of making strong, memorable mnemonics to pick weird things or things that aren’t normal. Things that will be easy to remember because they’re not part of your day to day, as far as characters that can get up to ridiculous situations and make sticky memories in your mind’s eye. The more ridiculous, generally, the easier it will be to remember who and what.

You can certainly make up your own mnemonics, you’ll just have to expend a little more effort every time you encounter a new thing that needs a new character/place/action/meaning combo.

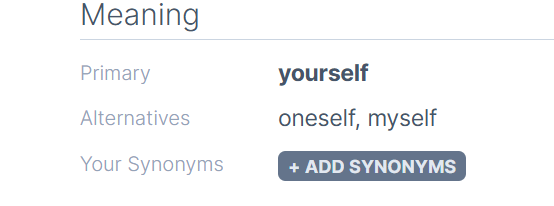

And since you can add your own meanings for everything, you can make it work if you do want to go your own way on mnemonics.

If you google some things on memory palaces and memory competitions, those share a lot of the same foundations that make something like HanziHero and Wanikani or their progenitor, James Heisig’s Remembering the Kanji/Hanzi books, work so well.

Thanks for your response. I hear ya, people can always make their own mnemonics - but we’re here to learn these ones. And I’m trying to see if anyone has any insight into how they were constructed.

Like, not only are the English mnemonics mostly the incorrect sound altogether. But, they are trying to help native English speakers remember information they already know; like that the ‘p’ sound in the Pinyin spelling “péng” is pronounced ‘p’ as in Patrick Star. Yes, I know the English consonant p sounds like p lol. And that’s what the English mnemonics function as so far; teaching English speakers how to read English characters for Pinyin spelling. And with mostly incorrect sounds as they relate to the Mandarin pronunciation.

Also, if these are supposed to be mnemonics based in widely recognizable pop-culture, why do they all have links to Wikipedia articles? Why would I want to interrupt my learning to go to a different website and read an article about Patrick Star; a character the platform thinks is already something I know so much about, that I will associate it with the letter ‘p.’ (Which of course I do.)

It feels like parts of the platform were constructed using an LLM, rather than a person who knows both English and Chinese putting it together; let alone a language teacher. And if that’s the case, I just wanna know. Is this an AI constructed learning tool?

I get why the pronunciation mismatches might stand out, especially if you’re new and trying to be precise. We’ve all been there. I also felt the same way, and after some weeks, the patterns did start to click.

There is an element of “trust the process” involved in learning a language like this with a method like this, and so I’d say just do your best, stick with it, show up and do the reviews, and before you know it, you’ll be multiple levels in and know quite a few hanzi and vocab and will be in a good spot to start reading and working on grammar and turning into a literate Chinese speaker.

So, one reason there are links to Wikipedia is because not everyone knows the same things. Older or younger people may not know or understand the mostly Millennial-focused pop culture references. Or folks that are coming from different countries and may not get a lot of the US-centric cultural/content references.

I believe the devs (Kevin & Phil) wrote all these themselves, not an LLM.

You might find this page useful to read on the main site where Kevin and Phil talk about why they made some decisions on things: Mnemonic System for Learning Chinese Characters | HanziHero. There’s also some good info on the history of stuff around the forums here too if you’re willing to do some searching.

And I’d encourage you to explore all the rest of the links under that Product dropdown as well as the Docs.

Again, thanks for reaching out.

First, I think we’ll just have to agree to disagree about the importance of having accuracy. I think if you’re teaching a language, your info needs to be accurate. But the mistakes are many, and would be easy to catch if a person were writing them and saying them out loud. I see that one could, as a native speaker of English, stick with it; trust the process, kind of figure out where the platform is wrong, and work around it. That’s true. But this platform costs the same as WaniKani. So I expect it to be as accurate without me having to redo all the work it missed.

However, you were right for me to check out the articles and docs to learn more. The main ‘About’ page explains a lot. First, Kevin and Phil are the only operators. And neither are native Chinese speakers. They only started learning a few years ago. And they admit that this platform is not the best resource for learning the sounds of the characters. “And while we have audio for each character and word, we are certainly not the place to go to to practice listening!” I would say that overlaps with the written sounds as well.

So, I would say that given their level of expertise, they are probably both working professionals in web development or something like that. But not language experts. That’s why the platform looks like a nice, professional copy of WaniKani. But with only about 5 years language experience in the language you’re teaching, it explains why to a teacher, the execution feels off.

All things considered, its mostly a very good tool. I’ll keep using it and look out for new developments. It’s a well built system that emulates WaniKani well. But I’d love to see more staff that are native speakers and or educators to round it out.

Thanks again for your insight. Cheers!

To be honest, I agree with many of your points about the mnemonic characters not being the greatest. But for me, (and I had this experience with wanikani too), after the first few levels, my brain tends to sort of ‘bend into shape’ to take in character readings via phonetic-semantic associations or brute force + learning words, and I start ignoring the mnemonics for each character. I think even in the most theoretically ideal environment of mnemonic stories, where the sound portion consisted of 19 initials (∅ b p m f d t n l g k z c s h zh/j ch/q sh/x r) + 4 medials (∅ i u ü) + 3 vowels (∅ a e/o) + 5 finals (∅ i u n ng) + 5 tones (1 2 3 4 ∅), and each of these sounds had an anthropomorphized IPA symbol as its representative, I would eventually ditch the mnemonics as inefficient. I want to shout out HH for even bothering to include some of the sound in their mnemonics in a consistent fashion, when WK doesn’t do that despite Japanese also having a limited set of syllables - they just do an adhoc english word of questionable similarity for each individual mnemonic.

Welcome to the forum!

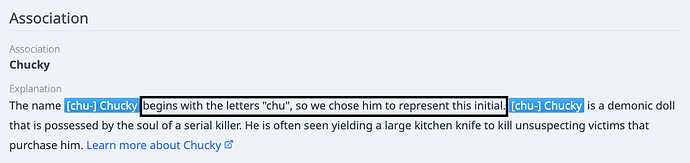

You would be correct to observe that the sound associations do not always reflect how the sound is actually pronounced in Chinese. We choose the sound associations by looking at both the phonetic and the actual written affinity – so in the case of Chucky, this association was chosen because it has the same letters [chu]. This is why we make sure to play the voice so you can hear what [chu] sounds like within the context of the pinyin system.

You can learn how each sound item was chosen by looking at the association explanation, for example [chu-] Chucky:

Associations which also have the same phonetic sound, such as in the case of [h-] Harry Potter, for example, is an added bonus, but is not the absolute rule for how we chose the associations.

Is there an argument to be made that we could’ve tried harder to find associations which have a closer phonetic mapping? Absolutely, but some sounds in Chinese have no English equivalent, so there’s no way to avoid this mismatch between the association and the actual pronunciation (as in the case of [ju-] Julius Caesar, for example.)

All of the mnemonics were handwritten over the course of a few years ![]()

Hope this helps ![]()